Table of Contents

The Late Uruk Period

Introduction

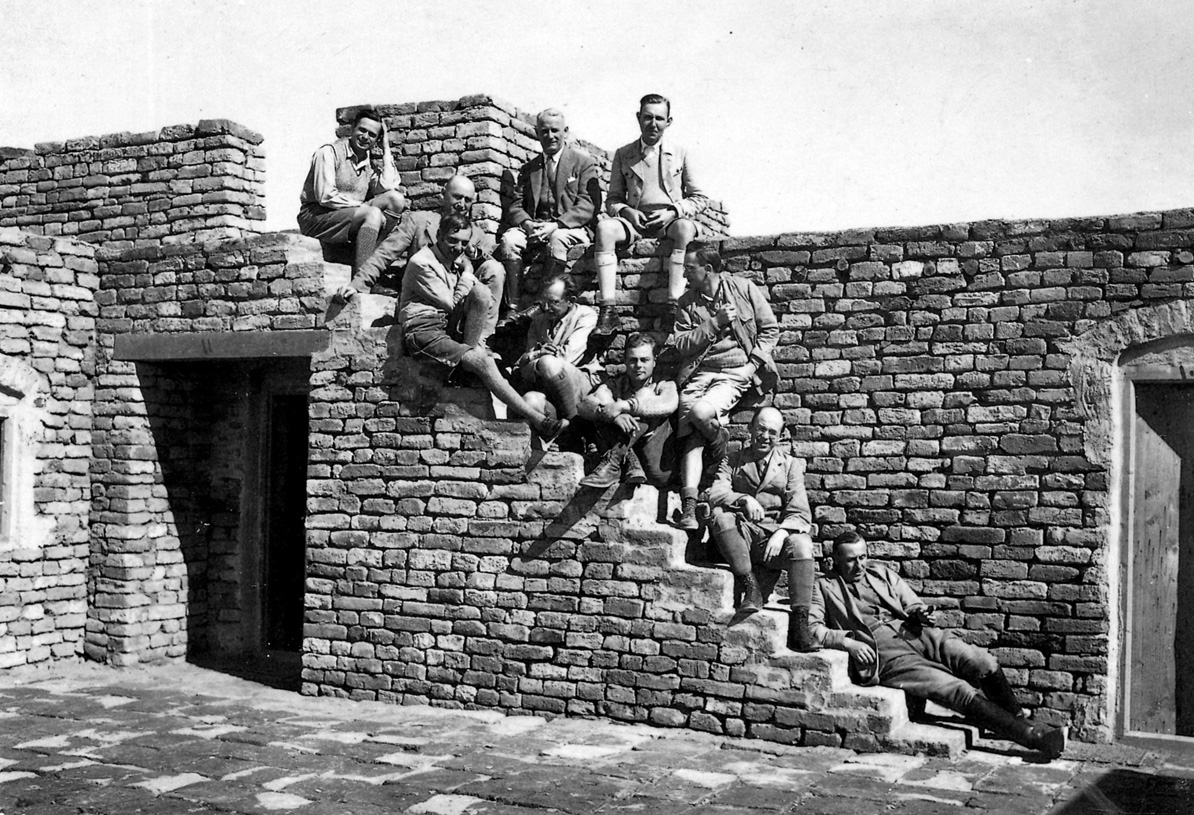

The earliest true script in man's history emerged at the end of the fourth millennium B.C. in ancient Babylonia, the southern part of today's Iraq. The signs of this script were impressed with the aid of a stylus into the still soft surface of clay tablets. Such clay tablets hardened almost immediately in the dry and hot climate of that part of the world. As a result of this hardening, and because such lumps of clay could not be reused, these documents from early Babylonia survived in great numbers. The early script developed into the better-known "cuneiform," the hallmark of Babylonian history and culture; hence the name "proto-cuneiform" has been accepted by most scholars to designate the archaic script. Most of the tablets of this early phase were found during the excavations in the ancient city of Uruk in lower Babylonia, conducted by the German Archaeological Institute from 1913 up to the present day and interrupted only by the two world wars, and by regional conflicts (the current director of German excavations, M. van Ess, recently reported [personal communication] that Warka has not been a target of successful plunderings in Iraq during the 2003 occupation of that country, unlike the sites of ancient Umma, Adab, Isin and Nippur). During the seasons from 1928 until 1976, nearly 5000 such tablets and fragments were unearthed, forming the basic material for a long-term research project dedicated to the decipherment and edition of these texts.

The dates and circumstances of discovery of the archaic tablets from Uruk

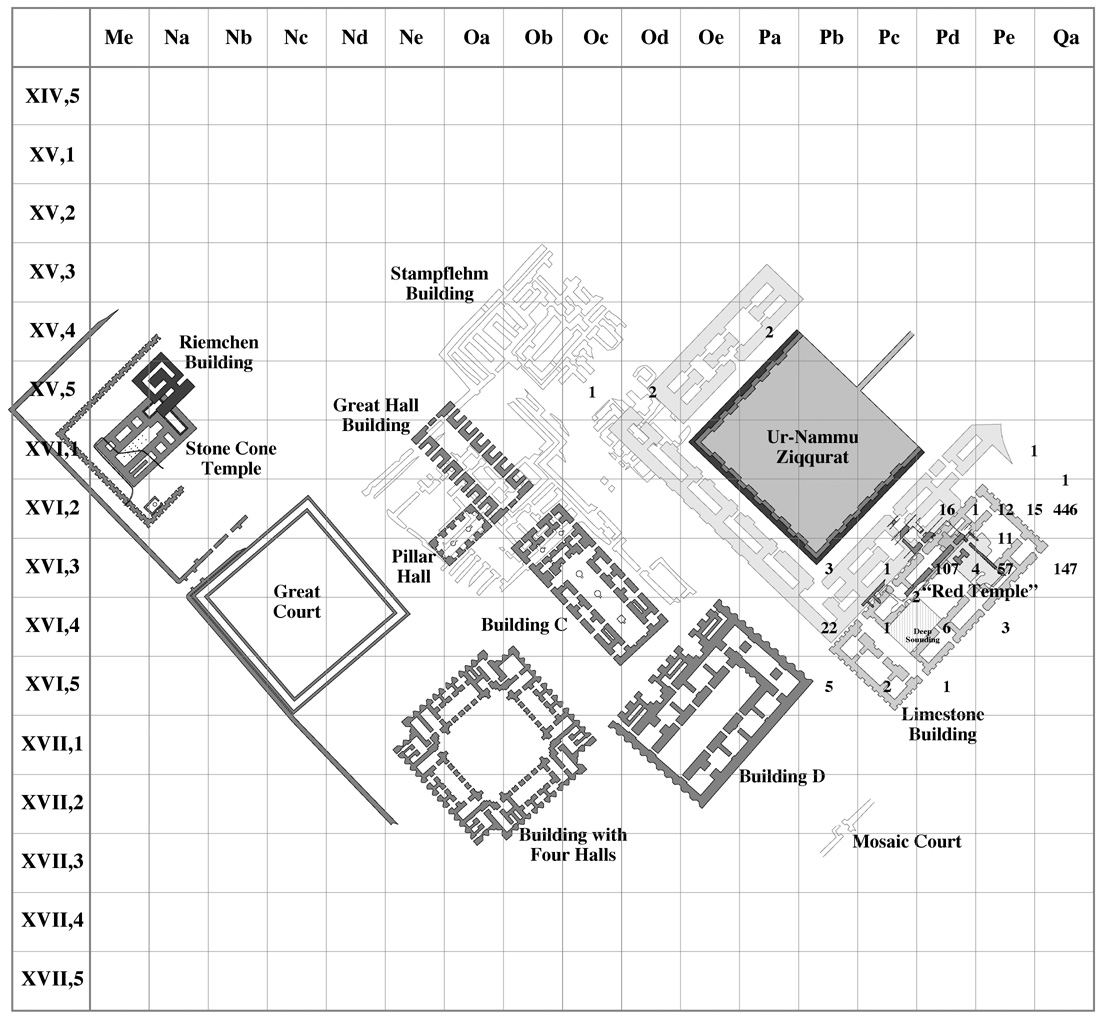

The most prominent archaeological site of the Late Uruk period is the ancient city of Uruk, today a vast landscape of ruins in southern Babylonia. Since early in the twentieth century, German archaeologists have been carrying out excavations at regular intervals at the site (with interruptions during the two world wars and regional conflicts), which was continuously occupied from the fifth millennium B.C. until its abandonment in the fifth century A.D. For the time before 2000 B.C., eighteen archaic layers, counting from top to bottom, were identified within Eanna, the central, sacred precinct of the city. Those layers numbered VIII to IV were ascribed to the Late Uruk period, layer III to the Jemdet Nasr period. Layer I with its subphases dates to the Early Dynastic period (layer II turned out to have been an erroneous designation and has therefore been excluded from current terminology).The extensive buildings of the Uruk III levels were erected on great terraces after the older buildings had been razed and their grounds leveled. Thus, surface pits and holes were filled with cultural waste, consisting of weathered and broken mud-bricks as well as ash, animal remains, pottery sherds, and the like.

This debris had apparently been taken from large waste deposits located elsewhere, which seemingly had been left by the great storage facilities from the lower levels whenever they were cleared of refuse. In this manner, large amounts of various kinds of once sealed objects found their way into the debris. After authorized individuals had broken sealed stoppers or collars in order to gain access to the stored contents of containers, the fragmented sealings may have been kept somewhere for control purposes but then lost their purpose and were consequently disposed of.Written documents were unquestionably treated in the same way. They served to carry out future checks on, for example, the amounts of barley delivered to a particular granary on a specified day or to keep track of the amounts of barley or beer distributed to named laborers. After a certain time had lapsed, this information was no longer useful. Consequently, the tablets were probably thrown away at regular intervals, thus landing on the refuse heaps. Judging from the distribution and concentration of tablets in various areas of Eanna unconnected to major buildings as well as from the random distribution of lexical texts, it seems clear that no contextual relationships existed between certain buildings and groups of texts.

Since the tablets had become irrelevant before they were disposed of in the rubbish dump that was used as a source of fill for surface irregularities of the large terrace below the buildings of Archaic Level III, they were obviously older than the earliest subphase of that layer. Although we are left in the dark as to their exact date or origin, we can assume that they are not older than the buildings of Archaic Level IV, since no tablets were found in the layers below them. Unfortunately, we cannot establish a stratigraphic link between the tablets and any of the three subphases "c," "b," or "a" of Archaic Level IV. In order to get a better grasp of the dates of these texts, we are thus obliged to develop new criteria based predominantly on the internal evolution of the script itself. In short, these findings suggest that there is scarcely enough time between the oldest tablets of script phase IV and the tablets of phase III to support the existence of an intermediate period between the two. The text corpus of script phase IV, moreover, seems itself so homogeneous that one is inclined to date all its tablets to a relatively short period. It therefore seems most likely that the period of the beginning of writing is more or less contemporary with the last of the stratigraphic subphases of archaic building layer IV, that is, with level IVa. Similar observations apply to another group of tablets from the period of archaic building level III. A considerable number of these texts were found in layers of debris upon which the buildings of layer IIIa were erected. The proposed dating of these tablets to the period of the preceding layer IIIb therefore seems quite plausible. Despite the relatively safe assignment of these tablet groups to the archaic building layers IVa and IIIb, we have been forced to abandon the habit of referring to them as tablets from the respective levels. In order to stress that the dates of the tablets were not established as the result of a direct link between them and their stratigraphic location, we modified the terminology slightly to indicate the paleographic development of the script employed in the texts. Consequently, we date the archaic tablets according to their respective evolutionary phase of script. In reference to the stratigraphic nomenclature, these have been called script phase IV and III.3-1.

The tablets from Uruk, however, are not the only archaic documents known from this period. Similar tablets have been found in the northern Babylonian site of Jemdet Nasr, and some few originate from the sites of Khafaji and Tell Uqair, likewise situated in the northern part of Babylonia. Further, regular and irregular excavations conducted during the 1990s have resulted in the discovery of ca. 400 more archaic texts. These tablets appear to have come from the ancient cities of Umma, Adab and possibly Kish. Although their overall number is small in comparison to the corpus from Uruk, they share a great advantage for our research efforts. Whereas all of the Uruk tablets, found in dumps where they had been discarded after they were no longer of use, were as a rule in a fragmentary state, the tablets from the other sites were often fully preserved, presenting us with their complete original information. Since we are faced with the problem of describing texts of an unknown language, most arguments about their contents have to be derived from the internal context of the tablets themselves. Textual analysis thus depends on information as complete as possible. The number of completely preserved tablets available to us has been considerably augmented recently. Toward the end of 1988, a group of 82 archaic tablets, formerly part of the Swiss Erlenmeyer Collection in Basel, was auctioned off in London. Although their existence had been known since their purchase by the Erlenmeyers in the late 1950s, these tablets had not been subjected to detailed study. The example below demonstrates the extraordinary level of preservation in this 5000+ year old artifact.

The work of the project Archaic Texts from Uruk

A long-term interdisciplinary research project Archaic Texts from Uruk, part of the efforts of the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative, is dealing with these issues. This project commenced in 1964, when Hans Nissen of the Free University of Berlin, began cataloguing and copying all archaic texts found in Uruk after the publication of a first lot by Adam Falkenstein in 1936. The archaic Uruk text corpus amounts to almost 5000 tablets and fragments. Beginning in 1984, a close cooperation evolved with the Center for Development and Socialization of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and Education, since reunification with the MPI for the History of Science, Berlin. The historian of science Peter Damerow, associate at these institutes, has concentrated his efforts on the question of whether the rich material pertaining to the period of early literacy in the ancient Near East may solve problems of cognitive psychology. Damerow has been concerned with the origin of mental structures, in particular the concept of number and the possible influence of culture-specific representations of cognitive systems on the development of such structures.This cooperation had its impact on procedures and methods of the Uruk Project. As a result of our diverse perspectives in approaching the sources, new methodological concepts have arisen. On the more practical level, this led to the intensification of the use of electronic aids, and in particular to the application of programming methods of artificial intelligence to the analyses of text transliterations and to the text-editing process. Increasingly, the traditional techniques of drawing the individual signs or entire texts were replaced by methods using computer graphics. This interdisciplinary cooperation had consequences for the study of the contents of the archaic texts, insofar as these combined efforts are targeted to research goals beyond the philological analysis of the written material. The decipherment of ancient written sources traditionally presents the researcher with one of three goals: the decipherment of a script, the language of which is known; the decipherment of a language when the script is known; and the decipherment in cases where neither script nor language are known but enough textual material is available that an attempt can be launched to decipher one or the other, or both. This classification enjoys only limited application in the case of the earliest form of writing in the Near East, since we know that it did not originate as a means of rendering language but as a monitoring instrument for the purpose of the administration of household economies. It is thus questionable whether or to what extent we can expect to find the traditionally close link between language and archaic script. Obviously, this limits the potential of a traditional philological approach in the form most cogently described by the eminent University of Chicago scholar Ignace Gelb in his Study of Writing (Chicago 1952).

We can only speculate to what degree social organization and ways of thinking were influenced by the beginning of literacy. This innovation was quite certainly more than a simple change in the means of storing information, or in the representation of language. Observing that at the end of the 3rd millennium B.C., during the so-called Ur III period, the human labor force was subjected to complete administrative control made possible through the developed techniques of writing, we must realize that this level of centralization would have been impossible without the methods of information processing developed more than 1000 years earlier. Incidentally, there is more than one comparison with our timeÑwhich has witnessed the second revolution in data processing–because then as now the development began with arithmetical techniques and not with a need to proliferate knowledge or linguistic communication. Yet, now as then the most dramatic effects of this revolution are felt in the processing of knowledge. Obviously such concepts involved in the study of the origin of writing are beyond the traditional realm of philology; yet it is equally obvious that any study without a solid philological background would be condemned to failure. The phenomenon of the origin of writing demands an interdisciplinary approach such as we have enjoyed in Berlin; perhaps our approach is not even diversified enough. It derives from our conviction that deciphering the archaic documents does not mean to merely translate them into a modern language, because they were not primarily meant to render language. Decipherment for us rather means the reconstruction of the social context and function of the documents, the study of the dynamics of the development of writing toward a comprehensively applicable instrument of intellectual life, and the examination of the consequences this development had for our way of thinking and our treatment of information. The early documents can thus be freed of some of their ambiguity, but also of their apparent simplicity, and so become early witnesses of the origin and the basic structures of our literate culture.

H. Nissen (adapted from Archaic Bookkeeping, pp. ix-x)

Bibliography

- Adams, R., Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Foodplain of the Euphrates (Chicago 1981)

- Adams, R., Nissen, H., The Uruk Countryside: The Natural Setting of Urban Societies (Chicago 1972)

- Algaze, G., "The Uruk Expansion: Cross-Cultural Exchange in Early Mesopotamian Civilization," Current Anthropology 30 (1989) 571-608

- Algaze, G., The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization (Chicago 1993)

- Allotte de la Fuÿe, C., Documents présargoniques (Paris 1908-20)

- Allotte de la Fuÿe, C., "Mesures agraires et calcul des superficies," RA 27 (1930) 65-71

- Amiet, P., "Il y a 5000 ans les Elamites inventaint l'écriture," Archaeologia 12 (September-October 1966) 16-23

- Amiet, P., Glyptique susienne, des origines ˆ l'époque des Perses achéménides: cachets, sceaux-cylindres et empreintes antiques decouverts a Suse de 1913 a 1967 (=Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique en Iran 43; Paris 1972)

- Arcari, E., La lista di professioni "Early Dynastic LU A": esempio di metodo di analisi dei rapporti tra le scuole scribali del III millennio a.C. (Naples 1982)

- Arcari, E., "Sillabario di Ebla e ED LU A: Rapporti intercorrenti tra le due liste," OrAnt. 22 (1983) 167-178

- Archi, A., La "Lista di Nomi e Professioni" ad Ebla, SEb 4 (1981) 177-204

- Archi, A., "The "Names and Professions List": More Fragments from Ebla," RA 78 (1984) 171-174

- Archi, A., "Position of the Tablets of Ebla, Or. 57 (1988) 67-69

- Baker, H., Matthews, R., Postgate, J. N., Lost Heritage: Antiquities Stolen from Iraq's Regional Museums, fascicle 2 (London 1993)

- Bartz, F., Die grossen Fischereiräume der Welt: Versuch einer regionalen Darstellung der Fischereiwirtschaft der Erde (Wiesbaden 1965)

- Bauer, J., Review of G. Selz, Die altsumerischen Wirtschaftsurkunden der Eremitage zu Leningrad (=FAOS 15; Wiesbaden 1989), in: AfO 36/37 (1989-1990) 76-91

- Behrens, H., Loding, D., Roth, M. (ed.), dumu-é-dub-ba-a: Studies in Honor of Åke W. Sjöberg (=Occasional publications of the Samuel Noah Kramer Fund 11; Philadelphia 1989)

- Benito, C., "Enki and Ninmah" and "Enki and the World Order" (UPenn dissertation, Philadelphia,1969, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor 1977)

- Biggs, R., "The Abu Salabikh Tablets," JCS 20 (1966) 73-88

- Biggs, R., "Semitic Names in the Fara Period," Or. 36 (1967) 55-66

- Biggs, R., Inscriptions from Tell Abu Salabikh (=OIP 99; Chicago 1974)

- Black, J., "The Alleged "Extra" Phonemes of Sumerian," RA 84 (1990) 107-118

- Blegvad, H., Fishes of the Iranian Gulf (Copenhagen 1944)

- Blunt, A., A pilgrimage to Nejd, the cradle of the Arab race … (London 1881)

- Bodenheimer, F., Animal and Man in Bible Lands (Leiden 1960)

- Boessneck, J., "Tierknochenfunde aus Ishan Bahriyat (Isin)," in B. Hrouda, Isin-Ishan Bahriyat I (Munich 1977) 111-133

- Boessneck, J., "Tierknochenfunde aus Nippur," in Gibson, M., et al., Excavations at Nippur: Twelfth Season (=OIC 23; Chicago 1978) 153-187

- Boessneck, J., Kokabi, M., "Tierbestimmungen," in B. Hrouda, Isin-Ishan Bahriyat II (Munich 1981) 131-155

- Boessneck, J. Driesch A. von den, Steger, U., "Tierknochenfunde der Ausgrabungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Baghdad in Uruk-Warka, Iraq," BagM 15 (1984) 149-189

- Boisson, C., "Contraintes typologiques sur le système phonologique du Sumérien," Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 84 (1989) 201-233

- Braidwood, R., Howe, B., Prehistoric investigations in Iraqi Kurdistan (=SAOC 31; Chicago 1960)

- Brandes, M., Siegelabrollungen aus den archaischen Schichten in Uruk-Warka (=FAOS 3; Wiesbaden 1979)

- Bottéro, J., "Konservierung von Lebensmitteln," RlA 6 (1980-1983) 191-197

- Brekle, H., "Konventionsbasierte Kriterien der Buchstabenstruktur am Beispiel der Entwicklung der kanaanäisch-phönizischen zur altgriechischen Schrift," Kodikas/Code Ars Semeiotica 10 (1987) 229-246

- Brekle, H., "Some Thoughts on a Historico-Genetic Theory of the Lettershapes of our Alphabet," in Watt, W., ed., Writing Systems and Cognition: Perspectives from Psychology, Physiology, Linguistics, and Semiotics (=Neuropsychology and Cognition 6; Dordrecht 1994) 129-139

- Brice, W., "The Writing System of the Proto-Elamite Account Tablets of Susa," Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 45 (1962-1963) 15-39

- Buccellati, G., "Salt at the Dawn of History: The Case of the Bevelled-rim Bowls," in Matthiae, P., et al., eds., Resurrecting the Past (Leiden 1990) 17-40

- Burrows, E., Ur Excavations. Texts 2 (London 1935)

- Butz, K., "On Salt Again …: Lexikalische Randbemerkungen," JESHO 27 (1984) 272-316

- Butz, K., "Zur Terminologie der Viehwirtschaft in den Texten aus Ebla," in Cagni, L. (ed.), La lingua di Ebla (Naples 1981) 321-353

- Butz, K., "Landwirtschaft," RlA 6 (1980-83) 470-486

- Butz, K., Schröder, P., "Zu Getreideerträgen in Mesopotamien und dem Mittelmeergebiet," BagM 16 (1985) 165-209

- Cavigneaux, A., "Lexikalische Listen," RlA 6 (1980-1983) 609-641

- Cavigneaux, A., Le rôle de l'écriture, in S. Auroux, ed., La naissance des metalangages en Orient et en Occident (=Histoire des idées linquistiques 1; Mardaga 1989) 99-118

- Cavigneaux, A., "Die Inschriften der XXXII./XXXIII. Kampagne," BagM 22 (1991) 33-123 and 124-163

- Charvát, P., "Pig, or, on Ethnicity in Archaeology," ArOr. 62 (1994) 1-6

- Christie, A., An Autobiography (New York 1977)

- Christian, V., Altertumskunde des Zweistromlandes von der Vorzeit bis zum Ende der Achämenidenherrschaft (Leipzig 1940)

- Civil, M., "The Home of the Fish," Iraq 23 (1961) 154-175

- Civil, M., "From Enki's Headaches to Phonology," JNES 32 (1973) 57-61

- Civil, M., "The Sumerian Writing System: Some Problems," Or 42 (1973) 21-34

- Civil, M., "Studies on Early Dynastic Lexicography," OrAnt 21 (1982) 1-26

- Civil, M., Biggs, R., "Notes sur des textes sumériens archa„ques," RA 60 (1966) 1-16

- Clutton-Brock, J., Burleigh, R., "The Animal Remains from Abu Salabikh: Preliminary Report," Iraq 40 (1978) 89-100

- Collon, D., First Impressions: Cylinder Seals in the Ancient Near East (Chicago 1987)

- Collon, D., Reade, J., "Archaic Nineveh," BagM 14 (1983) 33-41

- Crawford, H., "Mesopotamia's Invisible Exports in the Third Millennium B.C.," World Archaeology 5 (1974-1975) 232-241

- Cros, G., Nouvelles fouilles de Tello, par le commandant Gaston Cros (Paris 1910-1914)

- Cutting, C., Fish Saving: A History of Fish Processing from Ancient to Modern Times (London 1955)

- Damerow, P., Review of D. Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing (Austin 1992), in: Rechtshistorisches Journal 12 (1993) 9-35

- Damerow, P., Abstraction and Representation: Essays on the Cultural Evolution of Thinking (Dordrecht-Boston-London 1996)

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., "Die Zahlzeichensysteme der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk," in Green, M., Nissen, H., Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk (=ATU 2; Berlin 1987) 117-166

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., The Proto-Elamite Texts from Tepe Yahya (=American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 39; Cambridge, MA, 1989)

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., "Bemerkungen zu den vorangehenden Aufsätzen von A. A. Vaiman unter Berücksichtigung der 1987 erschienenen Zeichenliste ATU 2," BagM 20 (1989) 133-138

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from the Erlenmeyer Collection (=MSVO 3; Berlin forthcoming)

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., Nissen, H., "Die Entstehung der Schrift," Spektrum der Wissenschaft February 1988, 74-85

- Damerow, P., Englund, R., Nissen, H., "Die ersten Zahldarstellungen und die Entwicklung des Zahlbegriffs," Spektrum der Wissenschaft March 1988, 46-55

- Damerow, P., Meinzer, H.-P., "Computertomographische Untersuchung ungeöffneter archaischer Tonkugeln aus Uruk W 20987,9, W 20987,11 und W 20987,12," BagM 26 (1995) 7-33 + plts. 1-4

- Dandamaev, M., Slavery in Babylonia: From Nabopolassar to Alexander the Great (626-331 B.C.) (DeKalb, IL, 1984)

- Daniels, P., Bright, W. (ed.), The World's Writing Systems (New York 1996)

- Deimel, A., Die Inschriften von Fara I: Liste der Archaischen Keilschriftzeichen (=WVDOG 40; Leipzig 1922)

- Deimel, A., Die Inschriften von Fara II: Schultexte aus Fara (=WVDOG 43; Leipzig 1923)

- Deimel, A., Die Inschriften von Fara III: Wirtschaftstexte aus Fara (=WVDOG 45; Leipzig 1924)

- Deimel, A., Die Viehzucht der ‚umerer zur Zeit Urukaginas, Or. 20 (1926) 1-61

- Delitzsch, F., Handel und Wandel in Altbabylonien (Stuttgart 1910)

- Delougaz, P., The temple oval at Khafajah (=OIP 53; Chicago 1940)

- Delougaz, P., Pottery from the Diyala Region (=OIP 63,; Chicago 1952)

- Delougaz, P., Kantor, H. (ed. by A. Alizadeh), Chogha Mish (=OIP 101; Chicago 1996)

- Diakonoff, I., "Etnieskij i social'nyi factory v istorii drebnego mira (na materiale šumera)," VDI 84/2 (1963) 167-179

- Diakonoff, I., "Main Features of the Economy in the Monarchies of Ancient Western Asia," 3ème conférence internationale d'histoire économique, Munich 1965 (Paris 1969) 13-32

- Diakonoff, I., "Slaves, Helots and Serfs in Early Antiquity," ActAntH 22 (1974) 45-78

- Diakonoff, I., "Some Reflections on Numerals in Sumerian: Towards a History of Mathematical Speculation," JAOS 103, 1983, 83-93

- Dijk, J. van, "Ein spätaltbabylonischer Katalog einer Sammlung sumerischer Briefe," Or. 58, 1989, 441-452

- Dittmann, R., Seals, Sealings and Tablets, in Finkbeiner, U., Röllig, W., eds., Gamdat Nasr: Period or Regional Style? (=Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Reihe B 62; Wiesbaden 1986) 332-366

- Dittmann, R., Betrachtungen zur Fruehzeit des Südwest-Iran: Regionale Entwicklungen vom 6. bis zum frühen 3. vorchristlichen Jahrtausend (=BBVO 4, Berlin 1986)

- Dreyer, G., U. Hartung. and F. Pumpenmeier, Das prädynastische Königsgrab U-j in Abydos und seine frühen Schriftzeugnisse (=Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, German Archaeological Institute, Section Cairo, vol. 86; Mainz 1998)

- Driel, G. van, "Tablets from Jebel Aruda," in G. van Driel, et al., eds., zikir šumim: Assyriological Studies Presented to F. R. Kraus on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Leiden 1982) 12-25

- Driesch, A. von den, "Fischknochen aus Abu Salabikh/Iraq," Iraq 48 (1986) 31-38

- Drilhon, F. Laval-Jeantet, Pr. M., Lahmi, A., "étude en laboratoire de seize bulles mésopotamiennes appartenant au Département des Antiquités Orientales," Colloques internationaux CNRS Préhistoire de la Mésopotamie 17-18-19 Décembre 1984, Editions du CNRS (Paris 1986,) 335-344

- Dumont, J., "La péche dans le fayoum hellenistique," Chronique d'Egypte 52 (1977) 125-142

- Dyson, R., "Chronologies du Proche Orient Ð Chronologies in the Near East: Relative Chronologies and Absolute Chronology 16,000 - 4,000 B.P," CNRS International Symposium, Lyon, France, 24-28 November 1986 (=BAR International Series 379; Oxford 1987) 648-649

- Edzard, D., "Sumerer und Semiten in der frühen Geschichte Mesopotamiens," Genaeva 8 (1960) 243

- Edzard, D., "Die Keilschrift," in Hausmann, U., ed., Allgemeine Grundlagen der Archäologie (Munich 1969) 214Ð221

- Edzard, D., "Keilschrift," RlA 5 (1976Ð1980) 544Ð568

- Edzard, D., Review of Green, M., Nissen, H., Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk (=ATU 2; Berlin 1987), in ZA 83 (1993) 136-141

- Eichmann, R., Uruk: Die Stratigraphie, Grabungen 1912-1977 in den Bereichen "Eanna" und "Anu-Ziqqurat", (=AUWE 3; Mainz 1989)

- Eichmann, R., Uruk: Die Architektur I, Von den Anfängen bis zur frühdynasitischer Zeit (=AUWE 14; Mainz 2008?)

- Ellison, R., "Diet in Mesopotamia: The Evidence of the Barley Ration Texts (c. 3000-1400 B.C.)," Iraq 43 (1981) 35-45

- id., "Some Thoughts on the Diet of Mesopotamia from c. 3000 - 600 B.C.," Iraq 45 (1983) 146-150

- Englund, R., "Administrative Timekeeping in Ancient Mesopotamia," JESHO 31 (1988) 121-185

- Englund, R., Verwaltung und Organisation der Ur III-Fischerei (=BBVO 10; Berlin) 1990

- Englund, R., "Archaic Dairy Metrology," Iraq 53 (1991) 101-104

- Englund, R., Review of D. Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing (Austin 1992), in Science 260 (11 June 1993) 1670-1671

- Englund, R., Review of B. Lafont and F. Yildiz, Tablettes cunéiformes de Tello au Musée d'Istanbul I (Leiden 1989), in AfO 40-41 (1993-1994) 98-103

- Englund, R., Archaic Administrative Texts from Uruk: The Early Campaigns (=ATU 5; Berlin 1994)

- Englund, R., "Late Uruk Period Cattle and Dairy Products: Evidence from Proto-Cuneiform Sources," BSA 8/2 (Warminster 1995) 33-48

- Englund, R., "Late Uruk Pigs and Other Herded Animals," in Finkbeiner, U., Dittmann, R., Hauptmann, H., eds., Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Vorderasiens (=Fs. Boehmer; Mainz 1995) 121-133

- Englund, R., "Regulating Dairy Productivity in the Ur III Period," Or 64 (1995) 377-429

- Englund, R., "Question Mark Retrieval," NABU 1995:38

- Englund, R., Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Diverse Collections (=MSVO 4; Berlin 1996)

- Englund, R., "Grain Accounting Practices in Archaic Mesopotamia," in Høyrup, J., Damerow, P., eds., Changing Views on Ancient Near Eastern Mathematics (=BBVO 19; Berlin 2001) 1-35

- Englund, R., Grégoire, J.-P., The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Jemdet Nasr (=MSVO 1; Berlin 1991)

- Englund, R., Nissen, H., Die lexikalischen Listen der archaischen Texte aus Uruk (=ATU 3; Berlin 1993)

- Evans, J., "The Exploitation of Molluscs," in P. Ucko, G. Dimbleby, The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals (London 1969) 479-484

- Fales, F., Krispijn, T., "An Early Ur III Copy of the Abu Salabikh "Names and Professions" List," JEOL 26, 1979-80, 39-46

- Falkenstein, A., Die Haupttypen der sumerischen Beschwörung, literarisch untersucht (=Leipziger Semitische Studien Neue Folge 1; Leipzig 1931)

- Falkenstein, A., Literarische Keilschrifttexte aus Uruk (Berlin 1931)

- Falkenstein, A., Archaische Texte aus Uruk (=ATU 1,; Berlin 1936)

- Falkenstein, A., "Archaische Texte des Iraq-Museums in Bagdad," OLZ 40 (1937) 401-410

- Felix, J. (ed.), Herodot (Munich 1963)

- Field, H., "Ancient Wheat and Barley from Kish, Mesopotamia," American Anthropologist 34 (1932) 303-309

- Field, H., The Track of Man; Adventures of an Anthropologist (Garden City, NY, 1953)

- Finkbeiner, U., Röllig, W., eds., Gamdat Nasr: Period or Regional Style? (=Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients Reihe B 62; Wiesbaden 1986)

- Finkel, I., "Inscriptions from Tell Brak 1984," Iraq 47 (1985) 187-201 + plts. 32-36

- Flannery, K., "Early Pig Domestication in the Fertile Crescent: A Retrospective Look," in Young, T. C., Smith, P., Mortensen, P., eds., The Hilly Flanks and Beyond: Essays on the Prehistory of Southwestern Asia, presented to *Robert J. Braidwood, November, 15, 1982 (=SAOC 36; Chicago 1983) 163-188

- Forbes, R., Studies in Ancient Technology III (Leiden 1965)

- Friberg, J., The Early Roots of Babyloni-an Mathematics (Göteborg 1978-1979)

- Friberg, J., "Numbers and Measures in the Earliest Written Records," Scientific American 250/2 (February 1984) 110-118

- Friberg, J., "Mathematik," RlA 7 (1987-1990) 531-585

- Friberg, J., Review of D. Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing (Austin 1992), in OLZ 89 (1994) 477-502

- Fraser, J., Travels in Koordistan, Mesopotamia, etc., Including an Account of Parts of Those Countries Hitherto Unvisited by Europeans (London 1840)

- Frayne, D., The Early Dynastic List of Geographical Names AOS 74 (New Haven 1992)

- Gelb, I. J., A Study of Writing (Chicago 1963)

- Gelb, I. J., "The Ancient Mesopotamian Ration System," JNES 24 (1965) 230-243

- Gelb, I. J., "Growth of a Herd of Cattle in Ten Years," JCS 21 (1967) 64-69

- Gelb, I. J., "From Freedom to Slavery," RAI 18 (1970) 81-92

- Gelb, I. J., "Prisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia," JNES 32 (1973) 70-98

- Gelb, I. J., "Methods of Decipherment," JRAS 1975, 95-104

- Gelb, I. J., "Definition and Discussion of Slavery and Serfdom," Ugarit-Forschungen 11 (1979) 283-297

- Gelb, I. J., "Terms for Slaves in Ancient Mesopotamia, Societies and languages of the ancient Near East," in Dandamayev, M. A., ed., Societies and Languages of the Ancient Near East: Studies in Honour of I.M. Diakonoff (Warminster 1982) 81-98

- Gelb, I. J., "Sumerian and Akkadian Words for String of Fruit," in G. van Driel, et al. (eds.), zikir šumim: Assyriological Studies Presented to F. R. Kraus on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Leiden 1982) 67-82

- Gelb, I. J., Steinkeller, P., Whiting, R., Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus (=OIP 104; Chicago 1991)

- Gibson, M., and Biggs R. (eds.), Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East (=BiMes 6; Malibu 1977)

- Gordon, C., The Ancient Near East (New York 31965)

- Graeve, M.-C. de, The Ships of the Ancient Near East (c. 2000-500 B.C.) (Leuven 1981)

- Green, M., "A Note on an Archaic Period Geographical List from Warka," JNES 36 (1977) 293-294

- Green, M., "Animal Husbandry at Uruk in the Archaic Period," JNES 39 (1980) 1-35

- Green, M., "The Construction and Implementation of the Cuneiform Writing System," Visible Language 15 (1981) 345-372

- Green, M., "Miscellaneous Early Texts from Uruk," ZA 72 (1982) 163-177

- Green, M., "Urum and Uqair," ASJ 8 (1986) 77-83

- Green, M., Nissen, H., Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk (=ATU 2; Berlin 1987)

- Grégoire, J.-P., Inscriptions et archives administratives cuneiformes (=MVN 10; Rome 1981)

- Hackman, G., Sumerian and Akkadian Administrative Texts: from Predynastic Times to the End of the Akkad Dynasty (=BIN 8; New Haven 1958)

- al-Hadithi, A., Optimal Utilization of the Water Resources of the Euphrates River of IraqU(=Arizona dissertation, University Microfilms; Ann Arbor 1979)

- Hall, H., La sculpture babylonienne et assyrienne au British Museum (=Ars Asiatica 11; Paris-Brussels 1928)

- Hallo, W., "A Sumerian Amphictyony," JCS 14 (1960) 88-114

- Harrison, D., The Mammals of Arabia (London 1964-1972)

- Hatt, R., The Mammals of Iraq, University of Michigan (=Museum of Zoology, Miscellaneous Publications no. 106; Ann Arbor 1959)

- Heimpel, W., "Sumerische und akkadische Personennamen in Sumer und Akkad," AfO 25 (1974-1977) 171-174

- Heinrich, E., Schilf und Lehm. Ein Beitrag zur Baugeschichte der Sumerer (=Studien zur Bauforschung 6; Berlin 1934)

- Heinrich, E., Sechster vorläufiger Bericht … Uruk-Warka … (=Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Jahrgang 1935, philosophisch-historische Klasse Nr. 2; Berlin 1935)

- Heinrich, E., Kleinfunde aus den archaischen Tempelschichten (=Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 1; Leipzig 1936)

- Heinrich, E., "Die Stellung der Uruk-Tempel in der Baugeschichte," ZA 49 (1950) 20-44

- Heinrich, E., Bauwerke in der altsumerischen Bildkunst (Wiesbaden 1957)

- Heinrich, E., Die Tempel und Heiligtuemer im alten Mesopotamien: Typologie, Morphologie und Geschichte (Berlin 1982)

- Hoch, E., "Reflections on Prehistoric Life at Umm an-Nar (Trucial Oman) Based on Faunal Remains from the Third Millennium BC," in Taddei, M. (ed.), South Asian Archaeology 1977/1 (Naples 1979) 589-638

- Hole, F., Flannery, K., and Neely, J. (eds.), Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain; An Early Village Sequence from Khuzistan, Iran (=Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, no. 1; Ann Arbor 1969)

- Höyrup, J., "Sumerian: The Descendant of a Proto-historical Creole? An Alternative Approach to the Sumerian Problem," Annali dell'Istituto Orientale di Napoli: Annali del Seminario di studi del mundo classico, Sezione linguistica 14 (1992) 21-72

- Höyrup, J., and Damerow, P. (eds.), Changing Views on Ancient Near Eastern Mathematics (=BBVO 19; Berlin 2001)

- Hruška, B., Sumerian Agriculture: New Findings (=Preprint Series of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science no. 26; Berlin 1995)

- Jacobsen, T., "Early political development in Mesopotamia," ZA 52 (1957) 91-140

- Jacobsen, T., "On the Textile Industry at Ur under Ibbi-Sîn," Studia Orientalia Ionni Pedersen dicata (=Fs. Pedersen; Copenhagen 1953) 172-187

- Jacobsen, T., "The lil2 of dEn-lil2," in Behrens, H., Loding, M., and Roth, M. (eds.), dumu-é-dub-ba-a Studies in Honor of Åke W. Sjöberg (=Occasional publications of the Samuel Noah Kramer Fund 11; Philadelphia 1989) 267-276

- Jasim, S., and Oates, J., "Early Tokens and Tablets in Mesopotamia: New Information from Tell Abada and Tell Brak," World Archaeology 17 (1986) 348-362

- Jestin, R., Tablettes sumériennes de Šuruppak conservées au Musée de Stamboul (Paris 1937)

- Jordan, J., "Aus den Berichten aus Warka: Oktober 1912 bis März 1913," MDOG 51 (April 1913) 47-76

- Jordan, J., "Aus den Berichten aus Warka: März bis Mai 1913," MDOG 53 (April 1914) 9-17

- Jordan, J., Uruk-Warka nach den Ausgrabungen durch die Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft (=WVDOG 51; Leipzig 1928)

- Jordan, J., Erster vorläufiger Bericht über die von der Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft in Uruk-Warka unternommenen Ausgrabungen (=Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Jahrgang 1929, philosophisch-historische Klasse Nr. 7; Berlin 1930)

- Jordan, J., Zweiter vorläufiger Bericht … (=APAW 1930/4; Berlin 1931)

- Jordan, J., Dritter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1932, Nr. 2, Berlin 1932

- Khalaf, K., Reptiles of Iraq, with some Notes on the Amphibians, Baghdad 1959

- Khalaf, K., The Marine and Freshwater Fishes of Iraq, Baghdad 1961. XXX corrected!

- Kiutigh, K., Goldstein, L., American Antiquity 55, 1990, 585-591. XXX unvollstaendig

- Kose, A., Walter Andraes Besuch in Uruk-Warka vom 18.12.1902, in Finkbeiner, U., Dittmann, R., Hauptmann, H. (ed.), Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte Vorderasiens, Fs. Boehmer, Mainz 1995, 299-306

- Kraus, F., Staatliche Viehhaltung im altbabylonischen Lande Larsa, Amsterdam 1966

- Kraus, F., Sumerer und Akkader, ein Problem der altmesopotamischen Geschichte, Amsterdam 1970

- Krebernik, M., Die Beschwörungen aus Fara und Ebla: Untersuchungen zur ältesten keilschriftlichen Beschwörungsliteratur, Hildesheim 1984

- Krebernik, M., Review of Green, M., Nissen, H., Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk, ATU 2, Berlin 1987, in OLZ 89, 1994, 380-385

- Krebernik, M., Nissen, H., Die sumerisch-akkadische Keilschrift, in Günther, H., Ludwig, O. (ed.), Schrift und Schriftlichkeit, Berlin 1994, 274-288

- Krecher, J., Eine unorthographische sumerische Wortliste aus Ebla, OrAnt. 22, 1983, 179-189

- Krispijn, T., Die Identifikation zweier lexikalischen Texte aus Ebla MEE III Nr. 62 und 63, JEOL 27, 1981-82, 47-59

- Kuckenburg, M., Die Entstehung von Sprache und Schrift. Ein kulturgeschichtlicher Überblick, Cologne 1989

- Labat, R., Manuel d'épigraphie akkadienne: signes, syllabaire, ideogrammes, Paris 61988

- Lafont, B., Yildiz, F., Tablettes cunéiformes de Tello au Musée d'Istanbul, datant de l'époque de la IIIe Dynastie d'Ur (ITT II/1, 617-1038), Publications de l'Institut historique-archéologique néerlandais de Stamboul LXV, Leiden 1989

- Landsberger, B., Die Fauna des alten Mesopotamien nach der 14. Tafel der Serie öAR-RA = öUBULLU, ASAW 6, Leipzig 1934

- Landsberger, B., The Beginnings of Civilization in Mesopotamia, Three Essays on the Sumerians, Los Angeles 1974

- Langdon, S., Excavations at Kish I, Paris 1924

- Langdon, S., Ausgrabungen in Babylonien seit 1918, Der Alte Orient 26, 1927, 3-75. XXX unvollstaendig ?

- Langdon, S., The Herbert Weld Collection in the Ashmolean Museum: Pictographic Inscriptions from Jemdet Nasr, OECT 7, Oxford 1928

- Langdon, S., A New Factor in the Problem of Sumerian Origins, JRAS 1931, 593-596

- Langdon, S., New Texts from Jemdet Nasr, JRAS 1931, 837-844

- Le Brun, A., Recherches stratigraphiques ˆ l'acropole de Suse, 1969-1971, CahDAFI 1, 1971, 163-216

- Le Brun, A., Vallat, F., L'origine de l'écriture ˆ Suse, CahDAFI 8, 1978, 11-79

- Lenzen, H., Die Entwicklung der Zikurrat von ihren Anfängen bis zur Zeit der III. Dynastie von Ur, Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft in Uruk-Warka 4, Leipzig 1942

- Lenzen, H., ZA 15, 1949, 1. XXX unvollstaendig

- Lenzen, H., Die Tempel der Schicht Archaisch IV in Uruk, ZA 49, 1950, 1-20

- Lenzen, H., Mesopotamische Tempelanlagen von der Frühzeit bis zum zweiten Jahrtausend, ZA 51, 1955, 1-36

- Lenzen, H., Die Architektur der Schickt Uruk Arch. III (Djemdet Nasr) in Eanna, StOr. 46 (1975) 169-191

- Lieberman, S., Of Clay Pebbles, Hollow Clay Balls, and Writing: A Sumerian View, AJA 84, 1980, 339-358

- Limet, H., L'Anthroponymie sumerienne dans les documents de la 3e dynastie d'Ur, Paris 1968

- Lloyd, S. Safar, F., Eridu, Sumer 3, 1947, 94. XXX unvollstaendig

- Lloyd, S. Safar, F., Eridu: A Preliminary Communications [sic] on the Second Season's Excavations, Sumer 4, 1948, 115-127

- Lloyd, S. Safar, F., Tell Uqair. Excavations by the Iraq Government Directorate of Antiquities in 1940 and 1941, JNES 2, 1943, 131-158 + plts

- Loftus, W., Travels and Researches in Chaldaea and Susiana, London 1857

- Mackay, E., Report on Excavations at Jemdet Nasr, Iraq, Field Museum of Natural History, Anthropology Memoirs I/3, Chicago 1931

- Mair, V., Modern Chinese Writing, in Daniels, P., Bright, W. (ed.), The World's Writing Systems, Oxford 1996, 200-208

- Margueron, J., Recherches sur les palais mésopotamiens de l'Age du bronze, Paris 1982

- Martin, H., Fara: A Reconstruction of the Ancient Mesopotamian City of Shuruppak, Birmingham 1988

- Marzahn, J., Altsumerische Verwaltungstexte aus Girsu/Lagash, VS 25, Berlin 1991

- Matthews, R., The World's First Pig Farmers, Pig Farming 33, March 1985, 51-55

- Matthews, R., Excavations at Jemdet Nasr, 1988, Iraq 51, 1989, 225-248 + plts. 33-34

- Matthews, R., Excavations at Jemdet Nasr, 1989, Iraq 52, 1990, 25-39

- Matthews, R., Clay Sealings in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia: a Functional and Contextual Approach, Diss. University of Cambridge, 1989

- Matthews, R., Jemdet Nasr: the Site and the Period, Biblical Archaeologist 55, 1992, 196-203

- Matthews, R., Cities, Seals and Writing: Archaic Seal Impressions from Jemdet Nasr and Ur, MSVO 2, Berlin 1993

- Meer, P. van der, Dix-sept tablettes semi-pictographiques, RA 33, 1936, 185-190

- Melekeshvili, G., Esclavage, féodalisme et mode de production asiatique dans l'Orient ancien, in Sur le "Mode de production asiatique", Centre d'études et de Recherches marxistes, Paris 1974, 257-277

- Meriggi, P., Altsumerische und proto-elamische Bilderschrift, ZDMG Spl. 1, 1969, 156-163

- Meriggi, P., La scrittura proto-elamica I-III, Rome 1971-74

- Meriggi, P., Der Stand der Erforschung des Proto-elamischen, JRAS 1975, 105

- Michalowski, P., Review of D. Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing, Austin 1992, in: American Anthropologist 95, 1993, 996-999

- Michalowski, P., Memory and Deed: The Historiography of the Political Expansion of the Akkad State, in Liverani, M. (ed.), Akkad, The First World Empire: Structure, Ideology, Traditions, Padua 1993, 69-90

- Michalowski, P., Writing and Literacy in Early States: A Mesopotamianist Perspective, in Keller-Cohen, D. (ed.), Literacy: Interdisciplinary Conversations, Cresskill, NJ, 1994, 49-70. XXX corrected !!!

- Millard, A., The Bevelled-Rim Bowls: Their Purpose and Significance, Iraq 50, 1988, 49-57

- Moorey, P. R. S., Kish Excavations 1923-1933, Oxford-New York 1978

- Mudar, K., Early Dynastic III Animal Utilization in Lagash: A Report of the Fauna of Tell al-Hiba, JNES 41, 1982, 23-34

- Mynors, H., An Examination of Mesopotamian Ceramics Using Petrographic and Neutron Activation Analysis, in Aspinall, A., Warren, S. (ed.), Proceedings of the 22nd Symposium on Archaeometry, School of Physics and Archaeological Sciences, Bradford 1983, 377-387

- Nagel, W., Getreide: Archäologie, RlA 3, 1957-71, 315-318

- Nagel, W., Frühe Grossplastik und die Hochkulturkunst am Erythräischen Meer, Berliner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 6, 1966, 1-54 + plts. I-XIV

- Nikol'skij, M., Dokumenty chozjajstvennoj ot²etnosti drevnejshej epochi Chaldei iz sobranija N.P Licha²eva, Drevnosti Vosto²nyja 3/II, St. Petersburg 1908. Edition: Selz, G., Altsumerische Verwaltungstexte aus Lagash, 1: Die altsumerischen Wirtschaftsurkunden der Eremitage zu Leningrad, FAOS 15/1, Stuttgart 1989. Addenda: Selz, G., ASJ 16, 1994, 217-226

- Nissen, H., Remarks on the Uruk IVa and III Forerunners, in Civil, M. (ed.), The Series lú = sha and Related Texts, MSL 12, Rome 1969, 4-8

- Nissen, H., Grabung in den Quadraten K/L XII in Uruk-Warka, BagM 5, 1970, 101-191

- Nissen, H., Aspects of the Development of Early Cylinder Seals, in Gibson, M., Biggs R. (ed.), Seals and Sealing in the Ancient Near East, BiMes. 6, 1977, 15-23

- Nissen, H., Bemerkungen zur Listenliteratur Vorderasiens im 3. Jahrtausend, in Cagni, L. (ed.), La lingua di Ebla, Naples 1981, 99-108

- Nissen, H., Grundzüge einer Geschichte der Frühzeit des Vorderen Orients, Darmstadt 1983

- Nissen, H., Ortsnamen in den archaischen Texten aus Uruk, Or. 54, 1985, 226-233

- Nissen, H., The Development of Writing and of Glyptic Art, in Finkbeiner, U., Röllig, W. (ed.) Gamdat Nasr: Period or Regional Style?, Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Reihe B 62, Wiesbaden 1986, 316-331

- Nissen, H., The Context of the Emergence of Writing in Mesopotamia and Iran, in Curtis, J. (ed.), Early Mesopotamia and Iran: Contact and Conflict 3500-1600 B.C., London 1993, 54-71

- Nissen, H., Katalog der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk, ATU 4, Berlin forthcoming

- Nissen, H., Damerow, P., Englund, R., Frühe Schrift und Techniken der Wirtschaftsverwaltung im alten Vorderen Orient, Berlin 21991

- id., Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East, Chicago 1993 (revised English edition of Frühe Schrift)

- Noegel, S., An Asymmetrical Janus Parallelism in the Gilgamesh Flood Story, ASJ 16, 306-308

- Nöldecke, A., et al., Vierter vorläufiger Bericht … Uruk-Warka …, Abhandlungen der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Jahrgang 1932, philosophisch-historische Klasse Nr. 6, Berlin 1932

- id., Funfter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1933, Nr. 5, Berlin 1934

- id., Siebenter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1935, Nr. 4, Berlin 1936

- id., Achter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1936, Nr. 13, Berlin 1937

- id., Neunter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1937, Nr. 11, Berlin 1938

- id., Zehnter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1939, Nr. 2, Berlin 1939

- id., Elfter vorläufiger Bericht …, APAW 1940, Nr. 3, Berlin 1940

- North, R., Status of the Warka Excavation, Or. 13, 1957, 185-255

- Oates, D., J., The Rise of Civilization, Oxford 1976

- Oates, J., et al., The Sea-faring Merchants of Ur?, Antiquity 51, 1977, 221-234

- Oppenheim, A. L., On an Operational Device in Mesopotamian Bureaucracy, JNES 18, 1959, 121-128

- id., Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, Chicago 1964

- Orthmann, W., Der alte Orient, Propyläen Kunstgeschichte 14, Frankfurt-Berlin-Vienna 1975

- Parpola, S., Transliterations of Sumerian: Problems and Prospects, in Karki, I. (ed.), Studia Orientalia 46, Fs. A. Salonen, Helsinki 1975, 239-257

- Parrot, A., RA 30, 1933, 175. XXX unvollstaendig

- id., Tello. Vingt campagnes de fouilles (1877-1933), Paris 1948

- id., Les fouilles de Mari. Quatorzième campagne, printemps 1964, Syria 42, 1965, 12

- Payne, S., Partial Recovery and Sample Bias: The Results of Some Sieving Experiments, in Higgs, E. (ed.), Papers in Economic Prehistory I, Cambridge 1972, 49-64. XXX unvollstaendig ?

- id., in Clason, A. (ed.), Archaeozoological Studies, Amsterdam-Oxford 1975, p. 13. XXX unvollstaendig

- Pettinato, G., L'Atlante Geografico del Vicino Oriente Antico attestato ad Ebla e ad Ab¬ êalŒbÚkh (I), Or. 47, 1978, 50-73

- id., Testi lessicali monolingui della Biblioteca L. 2769, MEE 3, Naples 1981

- id., Liste presargoniche di uccelli nella documentazione di Fara ed Ebla, OrAnt. 17, 1978, 165-178 + plts. 14-16

- Pomponio, F., The Fara Lists of Proper Names, JAOS 104, 1984, 553-558

- Porada, E., Iranian Art and Archaeology: A Report of the Fifth International Congress, 1968, Archaeology 22, 1969, 54-71

- Postgate, J. N., Excavations at Abu Salabikh, 1975, Iraq 38, 1976, 133-161

- id., Early Dynastic Burial Customs at Abu Salabikh, Sumer 36, 1980, 65-82

- Postgate, J. N., Moorey, P. R. S., Excavations at Abu Salabikh, 1975, Iraq 38, 1976, 133-169

- Potts, D., On Salt and Salt Gathering in Ancient Mesopotamia, JESHO 27, 1984, 225-271

- Powell, M., Sumerian Area Measures and the Alleged Decimal Substratum, ZA 62, 1972, 165-221

- id., Three Problems in the History of Cuneiform Writing: Origins, Direction of Script, Literacy, Visible Language 15, 1981, 419-440

- id., Salt, Seed, and Yields in Sumerian Agriculture. A Critique of the Theory of Progressive Salinization, ZA 75, 1985, 7-38

- Qualls, C., Early shipping in Mesopotamia, UColumbia dissertation, New York, 1981

- Reade, J., An Early Warka Tablet, in Hrouda, B., Kroll, S., Spanos, P. (ed.), Von Uruk nach Tuttul, Fs. Strommenger, Munich 1992, 177-179 + pl. 79

- Redding, R., The Faunal Remains, in H. Wright (ed.), An Early Town on the Deh Luran Plain, Excavations at Tepe Farukhabad, Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, no. 13, Ann Arbor 1981, 233-XXX

- Reimpell, W., Geschichte der babylonischen und assyrischen Kleidung, Berlin 1921

- Renfrew, J. , Cereals Cultivated in Ancient Iraq, BSA 1, 1984, 32-44

- Rivoyre, D. de, Les vrais arabes et leurs pays. Bagdad et les villes ignorées de l'Euphrate, Paris 1884

- Roaf, M., Paléorient 2, 1974, 501. XXX unvollstaendig

- Robinson, A., The Story of Writing: Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictographs, London 1995

- Röhr, H., Writing: Its Evolution and Relation to Speech, Bochum 1994

- Römer, W., Einführung in die Sumerologie, Nijmegen 1982

- Safar, F., Eridu: A Preliminary Report on the Third Season's Excavations, 1948-49, Sumer 6, 27-38

- Safar, F., Mustafa, M. A., Lloyd, S., Eridu, Baghdad 1981

- Salonen, A., Die Wasserfahrzeuge in Babylonien nach sumerisch-akkadischen Quellen (mit besonderer Berucksichtigung der 4. Tafel der Serie öAR-ra= Æubullu). Eine lexikalische und kulturgeschichtliche Untersuchung, StOr. 8/4, Helsinki 1939

- id., Nautica Babyloniaca Eine lexikalische und kulturgeschichtliche Untersuchung, StOr. 11/1, Helsinki 1942

- id., Die Fischerei im alten Mesopotamien nach sumerisch-akkadischen Quellen, AASF B166, Helsinki 1970

- Sampson, G., Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction, Palo Alto 1984

- Scheil, V., Textes élamites-sémitiques, MDP 2, Paris 1900

- id., Documents en écriture proto-élamite, MDP 6, Paris 1905

- id., Tablettes pictographiques, RA 26, 1929, 15-17

- Schmandt-Besserat, D., The Use of Clay Before Pottery in the Zagros, Expedition 16/2, 1974, 11-17

- id., An Archaic Recording System and the Origin of Writing, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies 1/2, 1977, 31-70

- id., The Envelopes that Bear the First Writing, Technology and Culture 21, 1980, 357-385

- id., From Tokens to Tablets: A Re-evaluation of the So-called "Numerical tablets", Visible Language 15, 1981, 321-344

- id., Before Numerals, Visible Language 18, 1984, 48-60

- id., The Origins of Writing: An Archaeologist's Perspective, Written Communication 3, 1986, 31-45

- id., Tokens at Susa, OrAnt. 25, 1986, 93-125 + plts. IV-X

- id., Before Writing, Austin 1992

- Schretter, M., Sumerische Phonologie: Zu Konsonantenverbindungen und Silbenstruktur, Acta Orientalia 54, 1993, 7-30

- Selz, G., Review of Hayes, J., A Manual of Sumerian Grammar and Texts, in OLZ 87, 1992, 136-148

- Selz, G., Mash-da-ri-a und Verwandtes. Ein Versuch über daÐri "an der Seite führen": ein zusammengesetztes Verbum und einige nominale Ableitungen, ASJ 17, 1995, 251-274

- Serjeant, R., Fisher-folk and Fish-traps in al-Bahrain, BSOAS 31, 1968, 486-514

- Shendge, M., The Use of Seals and the Invention of Writing, JESHO 26, 1983, 113-136

- Sigrist, M., Messenger Texts from the British Museum, Potomac, MD 1990

- Smith, J., Historical Observations on the Conditions of the Fisheries Among Ancient Greeks and Romans, and on Their Mode of Salting and Pickling Fish, U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries, Report of the Commissioner for 1873-4 and 1874-5, Washington 1876

- Sollberger, E., Sumerica, ZA 53, 1959, 2-8

- Steinkeller, P., Alleged GUR.DA = ugula-gésh-da and the Reading of the Sumerian Numeral 60, ZA 69, 1979, 176-187

- Steinkeller, P., On the Reading and Location of the Toponyms ¡Rx¡.KI and A.öA.KI, JCS 32, 1980, 23-33

- Steinkeller, P., On the Reading and Meaning of igi-k‡r and gœrum(IGI.GAR), ASJ 4, 1982, 149-151

- Steinkeller, P., The Administrative and Economic Organization of the Ur III State: The Core and the Periphery, in Gibson, M., Biggs, R. (ed.), The Organization of Power: Aspects of Bureaucracy in the Ancient Near East, SAOC 46, Chicago 1987, 19-41

- Steinkeller, P., Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Sonderband 1987, 11-27. XXX unvollstaendig

- Steinkeller, P., Review of Green, M., Nissen, H., Zeichenliste der Archaischen Texte aus Uruk, ATU 2, Berlin 1987, in BiOr. 52, 1995, 689-713

- Steinkeller, P., Review of Englund, R., Nissen, H., Die lexikalischen Listen der archaischen Texte aus Uruk, ATU 3, Berlin 1993, in AfO 42/43, 1995-96, 211-214

- Stol, M., Milk, Butter, and Cheese, BSA 7, 1993, 99-113

- Stol, M., Milch(produkte), RlA 8/3-4, 1994, 189-201

- Strommenger, E., Mesopotamische Gewandtypen von der Frühsumerischen bis zur Larsa-Zeit, Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica 2, 1971, 37-55

- Strommenger, E., Habuba Kabira: eine Stadt vor 5000 Jahren, Mainz 1980

- Strommenger, E., Kleidung: Archäologisch, RlA 6, 1980-83, 31-38

- Struve, V., Some New Data on the Organization of Labour and on Social Structure in Sumer during the Reign of the IIIrd Dynasty of Ur, in Diakonoff, I. (ed.), Ancient Mesopotamia: Socio-economic History, a Collection of Studies by Soviet Scholars, Moscow 1969, 127-172

- Sürenhagen, D., Relative Chronology of the Uruk Period, Bulletin of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies 25, May 1993, 57-70

- Szarzynska, K., Some of the Oldest Cult Symbols in Archaic Uruk, JEOL 30, 1987-88, 3-21

- Thesiger, W., The Marsh Arabs, London 1964

- Thomsen, M.-L., 'The Home of the Fish': A New Interpretation, JCS 27, 1975, 197-200

- Thureau-Dangin, F., Tablettes ˆ signes picturaux, RA 24, 1927, 23-29

- Tilke, M., Studien zur Entwicklungsgeschichte des orientalischen Kostüms, Berlin 1923

- Tosi, M., Catalogue to the exhibition of the Museo Nazionale d'arte orientale, 14.5 - 19.7.1981

- Tosi, M., Early Maritime Cultures of the Arabian Gulf and the Indian Ocean, in al-Khalifa, S., Rice, M. (ed.), Bahrain Through the Ages: The Archaeology, London 1986, 94-107

- Turnbull, P., Reed, C., The Fauna from the Terminal Pleistocene of Palegawra Cave. A Zarzian Occupation Site in Northeastern Iraq, Fieldiana Anthropology 63/3, 1974, 81-146

- Vaiman, A., Über die protosumerische Schrift, ActAntH. 22, 1974, 15-27

- Vaiman, A., Eisen in Sumer, AfO Beih. 19, 1982, 33-37

- Vaiman, A., Über die Beziehung der protoelamischen zur protosumerischen Schrift, BagM 20, 1989, 101-114

- Vaiman, A., Protosumerische Mass- und Zählsysteme, BagM 20, 1989, 114-120

- Vaiman, A., Die Bezeichnung von Sklaven und Sklavinnen in der protosumerischen Schrift, BagM 20, 1989, 121-133

- Vaiman, A., Zur Entzifferung der proto-sumerischen Schrift (Vorlaufige Mitteilung), BagM 21, 1990, 91-103

- Vaiman, A., Formale Besonderheiten der proto-sumerischen Texte, BagM 21, 1990, 103-113

- Vaiman, A., Die Zeichen é und L‘L in den proto-sumerischen Texten aus Djemdet-Nasr, BagM 21, 1990, 114-115

- Vallat, F., Les documents épigraphique de l'acropole (1969-1971), CahDAFI 1, 1971, 235-245

- id., Le matérial épigraphique des couches 18 ˆ 14 de l'acropole, Paleorient 4, 1978, 193-195

- Vanstiphout, H., An Essay on the 'Home of the Fish', Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 13, 1982, 311-319

- Veenhof, K., SAG.IL2.LA = saggilž, "Difference Assessed" on Measuring and Accounting in Some Old Babylonian Texts, in Durand, J.-M., Kupper, J.-R. (ed.), Miscellanea Babylonica, Fs. Birot, Paris 1985, 285-306

- Veldhuis, N., Review of Englund, R., Nissen, H., Die lexikalischen Listen der archaischen Texte aus Uruk, ATU 3, Berlin 1993, in BiOr. 52, 1995, 433-440

- Vito, R. di, Studies in Third Millennium Sumerian and Akkadian Personal Names: the Designation and Conception of the Personal God, Studia Pohl SM 16, Rome 1993

- Waetzoldt, H., Untersuchungen zur neusumerischen Textilindustrie, Rome 1972

- Waetzoldt, H., Zu den Strandverschiebungen am Persischen Golf und den Bezeichnungen der î¿rs, in: Schäfer, J., Simon, W. (ed.), Strandverschiebungen in ihrer Bedeutung für Geowissenschaften und Archäologie, Ruperto Carola Sonderheft 1981, Heidelberg, 159-184

- Waetzoldt, H., Zur Terminologie der Metalle in den Texten aus Ebla, in Cagni, L. (ed.), La lingua di Ebla, Naples 1981, 363-378

- Waetzoldt, H., Kleidung: Philologisch, RlA 6, 1980-83, 18-31

- Waetzoldt, H., Die Situation der Frauen und Kinder anhand ihrer Einkommensverhältnisse zur Zeit der III. Dynastie von Ur, AoF 15, 1988, 30-44

- Watelin, L., Langdon, S., Excavations at Kish IV 1925-1930, Paris 1934

- Waterman, J., The Production of Dried Fish, FAO Fisheries Technical Paper no. 160, Rome 1976

- Watt, B., Merrill, A., Composition of Foods, Agricultural Handbook No. 8, Washington, D.C., 1975

- Weiss, H., Young, T., The Merchants of Susa, Iran 13, 1975, 1-18

- Westbrook, R., Slave and Master in Ancient Near Eastern Law, Chicago-Kent Law Review 70, 1995, 1631-1676

- Westphal, H., Westphal-Hellbusch, S., Die Ma'dan: Kultur und Geschichte der Marschenbewohner im Sud-Iraq, Berlin 1962

- Wickede, A. von, Prähistorische Stempelglyptik in Vorderasien, Münchner vorderasiatische Studien 6, Munich 1990

- Wiggermann, F., Aan de wieg van het schrift: Mesopotamische spijkerschrifttabletten uit 2900-400 v.C., Exhibition catalogue, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 24.4.-9.6.1992

- Wilcke, C., Formale Gesichtspunkte in der sumerischen Literatur, in Lieberman, S., Sumeriological Studies in Honor of Thorkild Jacobsen, Fs. Jacobsen, AS 20, Chicago 1976, 205-316

- Wilcke, C., in Behrens, H., Loding, M., Roth, M. (ed.), dumu-e2-dub-ba-a Studies in Honor of åke W. Sjöberg, Occasional publications of the Samuel Noah Kramer Fund 11, Philadelphia 1989, 559-569

- Willie, O., Handbuch der Fischkonservierung, Hamburg 1949. XXX unvollstaendig ?

- Wölffling, S., Die Altertums- und Orientwissenschaft im Dienst des deutschen Imperialismus, Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift der Universität Halle XX/2, 1971, 85-95

- Yoshikawa, M., Review of Thomsen, M.-L., The Sumerian Language: An Introduction to its History and Grammatical Structure, Mesopotamia 10, Copenhagen 1984, in BiOr. 45, 1988, 499-509

- Zettler, R., Sealings as artifacts of institutional administration in ancient Mesopotamia, JCS 39, 1987, 197-240

- Zimansky, P., Review of D. Schmandt-Besserat, Before Writing, Austin 1992, in: Journal of Field Archaeology 20, 1993, 414-517